The Sanskrit expression neti neti (नेति नेति) means “neither this, nor that”, and is used to describe the nature of Brahman. Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu’s style can be described in a similar way, by listing the things that he consciously chooses not to do. The 1949 movie Late Spring was my first Ozu film. After about 15-20 minutes, I began to feel uneasy. Is the cameraman taking breaks for tea? The reason for this was that the camera almost never moves in Ozu’s movies. Ozu rarely tracks his camera, and never pans. ダメダメ(Dame, dame). And the usual tricks – shots from high angle, close ups, camera moving in circle around the actors – are nowhere to be seen. Moreover, most scenes are shot from low height, giving perspective of a person sitting on a tatami, the Japanese mat. Ozu also shoots most scenes from the same locations again and again. He never shoots dialogues from over the shoulder as is customary. He either shoots it from a distance, or from a mid shot with the person speaking directly to the camera. In short, Ozu breaks almost all rules that are considered sacred in filmmaking. Ozu always uses 50-mm lens that best approximates the human vision.

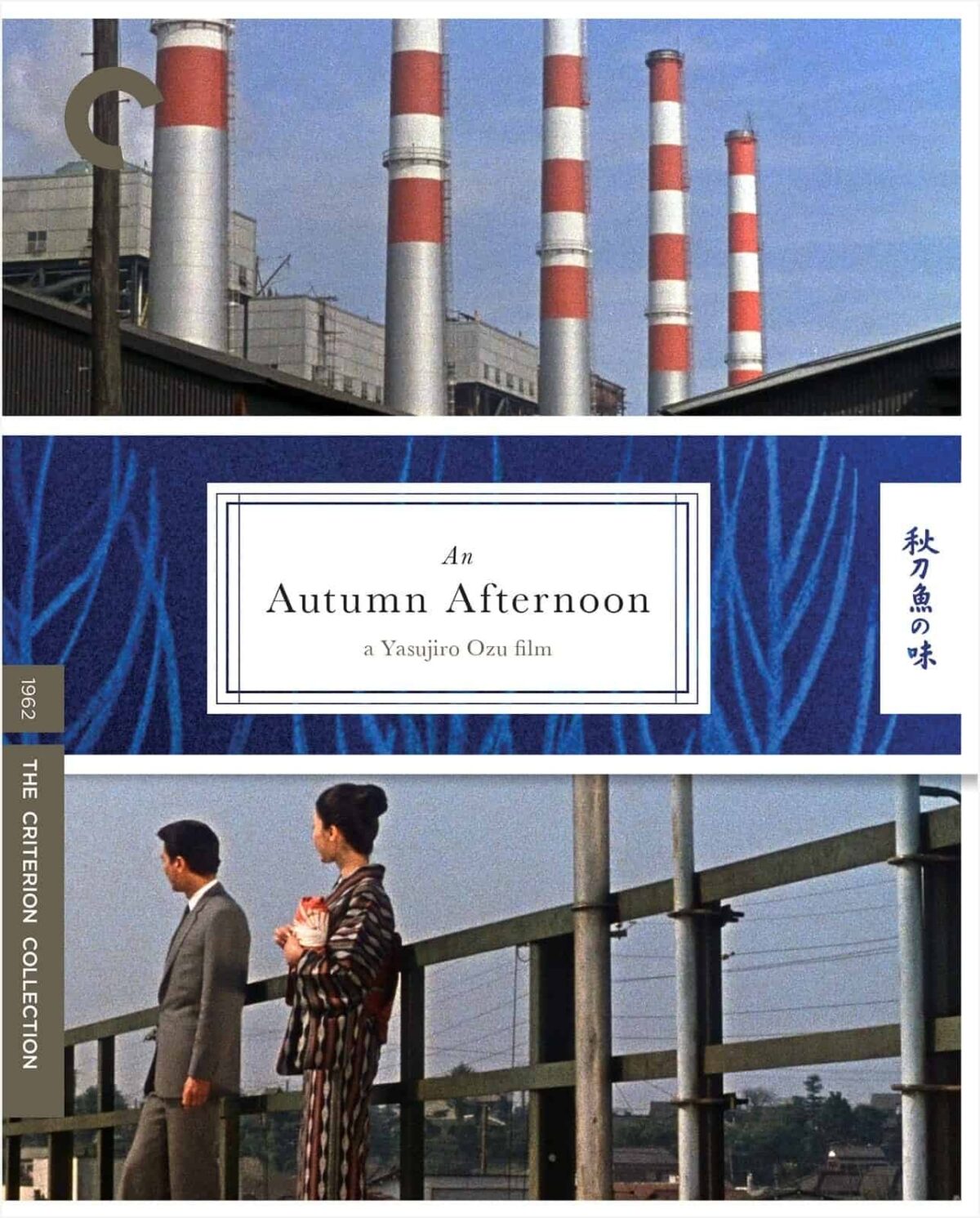

Ozu started with silent movies in 1927, adapting to talking movies and those with colour as technology progressed. His last movie, Sanma no aji (An Autumn Afternoon) was made in 1962. Ozu made movies belonging to the Gandai-geki genre that featured movies set modern times. This is in contrast to the Jidai-geki genre that features stories set in the Edo period, for instance, Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. Ozu’s characters never face unbelievable circumstances. Instead, they are everyday characters facing situations that are all too familiar. His stories can easily fit a paragraph or two and they contain no surprises or last minute reveals. Not only many of his stories repeat their themes, but even his lead characters are played by the same actors. In Ohayo (Good Morning), the main theme revolves around two little kids who want their parents to buy a TV set. Tokyo monogatari (Tokyo Story), one of Ozu’s most celebrated movies, is about parents from Kyoto who have come to visit their children in Tokyo and the difficulties they face in adapting to the fast city life and changed attitudes of their children.

Anton Chekhov famously said, “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.” Like many other sacred rules, Ozu does not care much for this one either. In Sanma no aji (An Autumn Afternoon), a waitress in a bar looks like the lead character’s dead wife. After coming home, he tells his children about this. In most movies, the waitress would be a significant part of the story. Not here. In the end, a vague reference suggests that this may be important but Ozu just leaves it there.

If you think all this is unconventional, there’s more. For instance, shooting a marriage is an opportunity ripe with all kinds possibilities for any filmmaker. Some movies are solely based on this premise. Ozu says, domo arigato but no. In Late Spring, and An Autumn Afternoon, the story revolves around the subject of daughter’s marriage. When the marriage finally happens, most directors would plan electorate scenes and sequences. What does Ozu do? He shoots people from both parties getting ready to go to the ceremony, and cuts it to people returning from the ceremony. We don’t even get to see the face of the groom! This idiosyncratic way of making movies is what sets Yasujirō Ozu apart from every other director.

What about acting? The actors in Ozu’s movies appear so natural that it takes time to realise that they are very talented. Few scenes – for instance when the lead character gets drunk – reveal the high quality of acting through tiniest of gestures.

Post-war Japan saw tremendous progress in science and technology that resulted in affluent and comfortable lifestyles. At the same time, many creative minds in Japan responded in their own way to a decline in moral values of the society. Kazuo Ishiguro documents it in An Artist of the Floating World. Haruki Murakami responds to it by abandoning the traditional Japanese values and culture, finding creative solace in western culture instead. Ozu’s post-war movies are about the individual struggles of the common man in that era of great upheaval.

Compared to modern day movies where every plot twist and every action is designed to generate maximum audience interest, Ozu may seem outdated. And yet, his movies have gained cult status with age. In 2012 Sight & Sound poll, Ozu’s Tokyo Story was voted third greatest film of all time by critics worldwide. So what makes these movies so interesting that they can be watched any number of times?

Framing and composition is everything for Ozu. His frames are like still life paintings. Many times, after the actors have exited the frame, the camera lingers on the empty frame, showing the room or the office or a narrow lane surrounded by shops with glittering neon signs. At other times, when the story moves from one location to next, Ozu lingers on the surroundings, capturing moon in a blue sky, a street light between two buildings or smoke coming out of chimneys. The location and its contents hold as much importance as the story and the actors.

Maybe this has something to do with the Japanese aesthetics – a set of ancient ideals that include wabi (transient and stark beauty), sabi (the beauty of natural patina and aging), and yūgen (profound grace and subtlety). When Yasujirō Ozu tells a story about a town, he also shows you how the town looks in the morning, how the train looks passing through that town and how a tiny alley blooms at night with neon signs from the shops. It is this aspect that gives depth and poignancy to all his narratives.

終